Sometimes, all it takes is a photograph to get me excited.

This was posted back in November of 2017 by one Shiv Saria. The tea in question was a Darjeeling white tea hailing from the Rohini tea estate. In most cases, that would be where the story ends, but if you’ve frequented this blog enough, you know there’s more to the story than that.

Unlike other white teas produced in Darjeeling, this wasn’t made using traditional Darjeeling clonals—like the aromatic AV2 or the old standby, T-78. Instead this was made from tea trees on an experimental plot, spearheaded by Shiv Saria and his son, populated entirely of Japanese cultivars. Yeah, you heard that right.

In the photo Shiv posted to Facebook, he mentioned this white tea—or “Japonica Bai Cha”as he called it—was the first invoice ever from this plot, and that the cultivars utilized were Yabukita and Fuzimidori respectively. Yabukita was ubiquitous in Japan, but I’d never heard of Fuzimidori.

I paid a visit to friend Ricardo Caicedo’s reliable Japanese cultivar database to verify. Nothing was listed. That could only mean one thing. If Ricardo hadn’t logged it . . . well . . .

Chances are, Mr. Saria meant Fukimidori, which is another common cultivar, but not as widespread as Yabukita. Other vendor sources who did order this particular invoice simply used Yabukita as the cultivar delineation. So, I’ll stick with that as well.

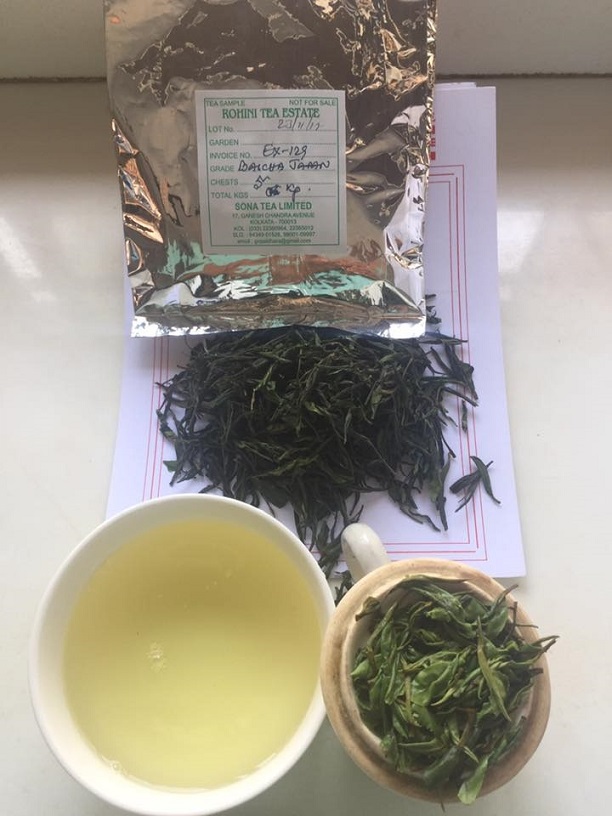

Nitpick aside, my curiosity was at half-mast. A photograph posted on Facebook several months later had me at a full-hoisted, ready-to-sail levels of intrigued. Peter Jones of Trident Booksellers & Café (in Boulder, CO.) posted this collage.

Same Japanese cultivar white tea, new invoice, spring first flush; my mouth watered a little onto my keyboard. A couple of months after that, Peter made note of my not-so-subtle interest and sent me some.

Around this time, I also (finally) did a skim-through on the history of the Rohini tea estate. Over the last few years, I’d tried several teas from them, even their signature white tea; Jethi Kupi. For one reason or another I’d never written about them, until now.

Like many Darjeeling gardens, Rohini was first planted and plotted over a century ago by the British. After Indian independence, the garden transferred to Indian owners. However, the estate shuttered in 1962, and wouldn’t be reopened until the early-2000s, when it was acquired by the Saria family-backed Sona Tea Group. The same family also owned and operated two Dooars plantations, and the much-older, continuously-running garden; Gopaldhara.

Of the original 1,300 hectares first planted, only 33 still possess the old tea plants, and only a total of 146 hecatares is actively propagated. Most of that is occupied by young tea bushes and clonals. In the span of a few decades, Rohini went from being one of the oldest estates, to the youngest.

I dipped into the white tea in the middle of July.

One of the things that really stuck out was how much of a sugarcane note the leaves possessed; both on the dry scent and when brewed. That also was the foremost note on introduction, and it continued throughout the sip. Another tea compatriot o’ mine one time noted that some Japanese cultivars possessed that note naturally. However, I never ran into that with Yabukita senchas from Japan. Something else was at play here. I needed another Rohini white tea, made from different cultivars, as a target for comparison.

As luck would have it, Trident Peter delivered again in November with this lovely downy-as-f**k white tea.

I consulted with Rishi Saria (Shiv’s nephew) of Gopaldhara to learn more about it. He mentioned it  wasn’t made from the usual Darjeeling cultivars, either. Rather, it was made from locally cultivated one called “Bhime”, and it had no official, numerical delineation like other cultivars. The way he put it, it was colloquially named by the locals after a hero from the Mahabharata—a man with magical strength named Bhima.

wasn’t made from the usual Darjeeling cultivars, either. Rather, it was made from locally cultivated one called “Bhime”, and it had no official, numerical delineation like other cultivars. The way he put it, it was colloquially named by the locals after a hero from the Mahabharata—a man with magical strength named Bhima.

Honestly, it was pretty apt. The smell on this stuff was strong. Every aromatic note the Japanese cultivar white had, this one had, too . . . but dialed up to eleven. Particularly the sugarcane sweetness. Part of that, I surmised, could’ve been due to the wild nature of the cultivar itself. Because it wasn’t an official, designated Darjeeling clonal, chances are it was as haphazardly monitored as Taiwan’s own Qing Xin.

That’s not to say it wasn’t regimented at Rohini, but just that the cultivar’s presence in Darjeeling proper was a mixed blessing. Whatever its origin, the result catered to a lovely white tea, and it stood to be a hefty comparative tea to the other white. Plus, it was plucked and processed around the same time; spring of 2018.

I didn’t get around to a comparison until February of 2019.

Obviously, the cuts on both of these white teas were different. The Japanese cultivar white was folded in a way to resemble a Chinese green, much like an An Ji Bai Cha. I read somewhere that this was due to the use of Chinese machines to process the tea. That would explain the “Bai Cha” in the name. (It literally means “white tea”, folks.)

The Bhime white had a wilder appearance, but I still liked the way that it was a whole leaf white tea. The young leaves were mostly, almost fully intact—save for a couple that had shredded edges. When brewed, and unfurled, the leaf quality was apparent. In this, it had a lot in common with the Japanese cultivar white. Steam aroma was also similar, if bolder.

For brewing, I subjected both to roughly 185°F brewed water, and a steep of about three minutes. My usual for Darjeeling whites. Considering these were both whole leaf white teas, they could take it. Or . . . so I hoped.

And take it, they did.

Both brewed up the same shade of light green, with similar sugarcane-like steam aromas. The Bhime was more pronounced than the Japanese, but the former seemed more layered. This tête-à-tête continued on in their respective palatial profiles as well. The Bai Cha was gentler, softer, more layered, spreading out its sweetness throughout the sip-‘n-slurp, whereas the Bhime delivered with a candied punch that slowly softened over time. The finish on both was similar and sublime.

It’s difficult to say which I liked better, as it often is. If anything, this shows a bit of what Darjeeling—as a region—has to do for future relevance. Diversify, experiment, and surprise; three factors that make for a great tea estate story. While writing this, I brewed both of them up a second time, and I’m on steep three of each . . . if you’ll excuse me . . .

Leave a Reply