Roughly a month ago, I received a package invoice in my business e-mail . . . and I wasn’t expecting one.

I get tea deliveries fairly frequently, but I clearly remember putting an unspoken moratorium on review samples. And I hadn’t bought anything. So, naturally, I was puzzled. The invoice was for no money, and a package was being sent my way from Joseph Wesley Tea. I had no problem with this development; JWT was awesomesauce incarnate. But I did want some clarification. So, I messaged to good ol’ Joe.

He confirmed that, indeed, a package was meant to be sent for me, and that it was a new item they were playing around with. A masala chai (spiced tea) kit, of sorts. It was a tin of JWT’s No. 2 Assam . . . and a traditional clay taster cup called a kullad. I’d never heard of it. The name sounded vaguely Klingon to me.

The titular Joseph informed me that they were clay cups traditionally used as one-shot, disposable teaware for serving chai. In fact, chaiwallahs still used them. Joseph Wesley Tea had partnered with potters in Bangelore to produce some with the tea company’s logo.

Back in the days when the traditional caste system was strictly enforced in India, kullads were designed to protect people from touching teaware that had been “tainted” by members of lower castes. After finishing one’s chai, one simply took the kullad and smashed it on the ground. The clay cup would then degrade on its own. In other words, the first biodegradable(-ish), disposable cup. Take notes, ‘Merica.

I received the package a week or so later . . .

But I didn’t break into it until a month after that.

Inside was the Assam, as advertised, and the li’l clay cup.

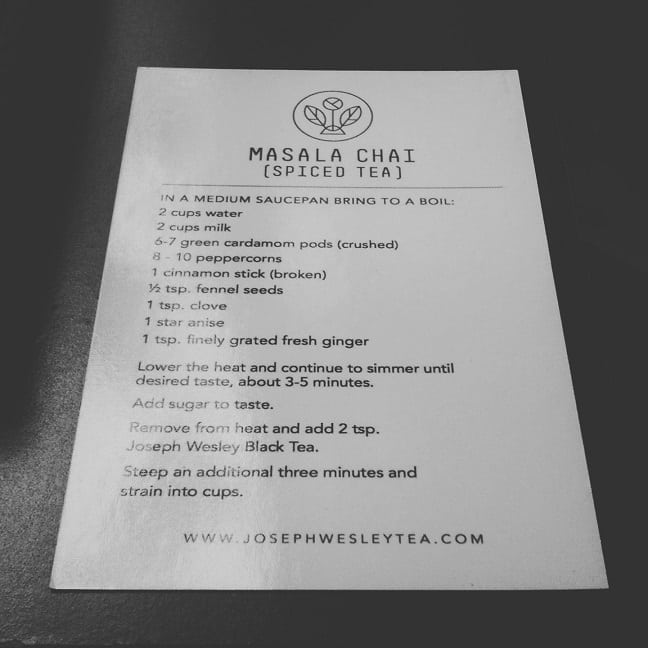

There were also instructions on how to make masala chai, but that made my eyes glaze over.

I just decided to brew up some straight Assam, and use the kullad for that purpose. I wasn’t much of a masala chai guy, anyway. And I was lazy.

The Assam that JWT carried hailed from the Hathikuli tea estate – one I hadn’t heard of. Not too far of a stretch, since the Assam region had hundreds of tea estates to choose from. What was surprising, though, was that it was organic. Aside from the Heritage garden, I didn’t know of many other organic Assam growers. That sort of label didn’t usually matter to me, but it was worthy of note.

The leaves looked typically Assam-ish – beige-to-brown, small, rolled and machine-cut. However, they possessed a slightly different aroma than Assams I’d sniffed before. I whiffed shades of earth, malt and something nutty. It was like smelling the aftermath of an unholy sexual union between a rock monster and a very large dark chocolate bar.

For brewing, I chose to put a teaspoon of leaves in a gaiwan . . . because it was first thing within reach from where I was sitting. I, then, poured boiled water over the leaves, and waited for about four minutes.

After that, I tried pouring the contents of the gaiwan into the kullad, which was a terrible idea. I wasn’t the most graceful of pourers, normally, but draining the contents of a wide-lipped gaiwan into a narrow clay cup? Instant FAIL.

Once I succeeded in filling the tiny cup, I sipped at length. Joe had warned that my lips might stick to the dry edge of the kullad, and he was right. But it wasn’t off-putting. I’d sipped from worse teaware. Something about the porous clay and the earth-malt-sweet Assam created a really mellow drinking session. Normally, Assam jolts me upright, like I was about to run from a pack of rabid wolves. Not so this time. I felt more of a calm wakefulness, a sensation usually associated with Chinese blacks. It was a very nuanced Assam in a very unusual (to me) cup.

Drinking from that li’l clay cup made me feel like I had somehow chosen to brew this wisely.

Er . . . minus the really ancient Crusader.

Leave a Reply