No one likes to talking about Burma . . . or Myanmar . . . or whatever it’s calling itself, now.

Even the name of the country is a hotly contested issue. At college parties, whenever some Eastern Philosophy major brought up Buddhism as an example of a nonviolent religion, all someone had to do was say, “Myanmar.” Or Burma. Or whatever!

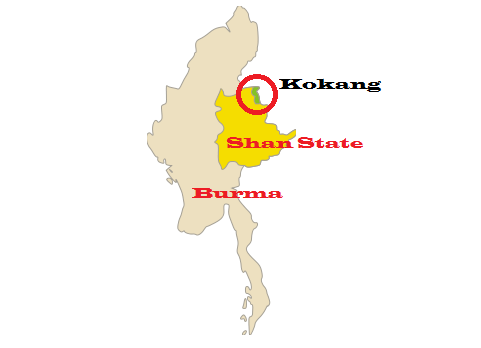

A microcosmic example of the country’s continuing struggle (with everything) is tea. The Shan State in northeastern Burma/Myanmar is considered its principle tea-growing area. The problem? It’s tough to verify that the fresh leaf being used to make Burmese tea is even grown there. Some validity, though, can be made for a smaller region within the Shan State, which shares a border with Yunnan province, China. That region is Kokang.

I first learned of this region through an article that was posted by Life in Teacup’s owner, Ginko Seto. In it, she detailed some of the bloodier events that had occurred in 2015, regarding the 2015 Kokang Offensive. For you see, Kokang —as a whole—has been a hotly contested territory since its incorporation. It was originally part of China . . . then it wasn’t . . . then it was again, and then it was “gift-wrapped” to communist Burma. For a short stint, it was autonomous, and it . . . kinda still is? (Emphasis on the question mark.) And while I hate to “yadda-yadda-yadda” the continuing conflict, I have to. Detailing the continuing strife in the region would take up this entire post.

On the upside, what is fascinating about Kokang is that 90% of the population is actually ethnically Han Chinese, and—at least, ecologically—it shares remarkable similarities with the rest of the Lincang region in Yunnan province, China. As a result, through osmosis and immigration, some of the ancient puerh tea processing practices remain there. Like Thailand and Laos, the border “hill tribes” have taken the growing, production and processing techniques of puerh-like teas and made them their own.

I wish ‘Merica’s hill tribes were so inventive.

To date, I hadn’t tried any “puerh” from Kokang. I say that with air-quotes because, technically, puerh-like teas not from Yunnan province can’t be considered puerh. Some (such as myself) give a pass to puerhs produced along Yunnan’s borders, but purists generally don’t. For the sake of this piece, I’ll go the purist route. These are heicha (dark tea), not puerh.

Okay, officially puerh is in the greater heicha family, a- . . . oooOOOOOOWWWW! Explaining this is a headache. Let’s move on.

I was able to procure—not one, but three—different Kokang offerings through What-Cha Tea; two raw, one cooked.

Since I was dealing with three heichas in a row, I opted out of a gongfu approach. Instead, I brought water to a boil, and then let it rest for a minute. I placed a chunk of each heicha in its own gaiwan, poured hot water over each, and then let ‘em steep for a minute. Then I sipped. These are the results:

2014 Sen Zhi Kui Kokang Raw Dark Tea

The 2014 pretty much looked like any other leaf clump that’d been chiseled off of a puerh beeng. The now-pressed leaves still retained their young greens and beiges, and the scent they gave off was subtle and wilderness-leaning. The only aspect where it differed from its Yunnan kin was the overall “wildness” of the aroma and leaf presentation. Everything still seemed rough, as if its youthfulness had yet to be tempered.

At a minute, the youngest raw was . . . well . . . young, spry and a li’l bit bitter on introduction.

But I chocked that and any requisite astringency on the minute-long brew. Other than that, the taste was stone-fruity, hemp-like, minty, and with a mossy finish. Very much in line with a young, yet-to-be-tested sheng puerh. There was also a slightly smoky lean throughout the sip that reminded me of . . . “dousing the campfire and continuing a hike.” Okay, I’ve never doused a campfire with water, and I never, ever hike. But if that feeling was diluted into a liquid, this would be it.

The 2006 raw couldn’t have been more different from its younger counterpart. The pressed leaves also retained their green palette, much to my surprise, but the scent was far older and far stronger. That and there was a bit of a “faded” aspect to its overall appeal. This felt like an older heicha, starting with the smell. The aroma was all must, spice and forgotten memories. And the faded greens also gave the beeng chisels an impression of . . . venison droppings. Very earthy. I was instantly drawn to it in an almost-Bear-Grylls-ish sorta way.

This one brewed darker than the 2014; same amber color, just more of it. The steam aroma matched the dry scent, note for note, save for a kelp-like lean and . . . something else. On taste, I found that “something else”. Oh man, where to start . . .

The intro started off like a ten-year-old puerh—herbaceous, slightly fungal . . . y’know, old—but then it went straight into parts unknown. That kelp-like thingy in the steam aroma punched my tongue in all its pressure points, invoking groans of palatial delight. I tasted seaweed, smoke, pipe tobacco after a pipe drag, kindling, and lumberjack fantasies. Of all the non-Chinese heichas I’ve tried . . . this was instantly my favorite.

There was no mistaking the shou/cooked heicha of the bunch. The 2013 came right on out with its dark brown-red leaves and strong, impatiently earthy aroma. There was a small sign of compost to the scent, but for the most part . . . it smelled like soil. No superlatives necessary. Appearance-wise, though, it reminded me of a Japanese heicha I tried a couple of years ago. The long, weirdly-pressed/twisted leaves resembled Batabatacha, although not as alluring. Or seaweed-like.

They say that a good cooked puerh needs to have a bright, if dark, color and smell/taste like jujubes. Well, I’ve never tasted a jujube, so I have no basis of comparison. However, I have sampled cooked/shou offerings that had a berry-seedlike taste, which I preferred. This possessed that. The color was dark enough, but not pitch-black like some other shous out there. Steam aroma was all earth and ocean shore—hit or miss, in my opinion. The true test of its character was in the taste.

It reminded me of a fragrant wood-pressed puerh I tried roughly a year ago. Not sure what they did to it, but there was a chocolate-covered fruit bend to the proceeding taste. This was like that and so much more. It possessed very little of that fish-like taste some poorly made cooked puerhs possessed, and nor was it overly earthy and soil-like. Nope, this was chocolate-covered espresso beans dipped in the life’s blood of a dancing California raisin.

My favorite?

Oh, that was the ’06, by a very large margin. A week or so ago, I even plopped some money down and bought an entire 100-gram cake of the stuff. Second was the cooked. While I’m not usually a shou puerh guy, it hit all the right palatial points. The 2014 was still a bit young and rough, and yet—oddly enough—it was the first of the three to sell out on What-Cha’s website.

In closing, I do hope Kokang finds some respite from conflict, soon. They’re producing some great teas there. I, for one, would like to see them continue to do so. Even if that means bringing up the elephant in the room.

To buy the 2006 Raw, go HERE.

To buy the 2013 Shu Cha, go HERE.

Leave a Reply