At the Portland Tea Festival in July (of this year, the time of this writing), Oolong Owl dragged me to a Japanese tea vendor booth. This was markedly weird for two reasons: one, the Owl rarely dragged—more like, prodded. Two: it was a Japanese tea vendor. I always assumed she was just a puerh stan. She never fails to surprise.

The man she introduced me to was Kei Nishida, purveyor of the Japanese Green Tea Company.

The outfit was exemplary for two reasons: they only sold tea from one garden. The second? Their western presence was right in my backyard.

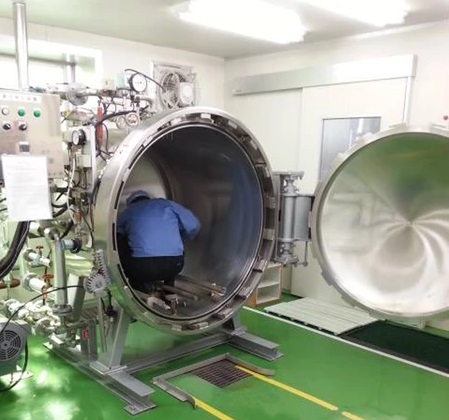

The farm they sourced from is called Arahataen, named for the founder Eizo Arahata. The 17-acre plot was crafted for tea in 1948. The farm is noteworthy for helping to perfect deep-steaming technology, and for introducing clean-room techniques to Yunnan for the production of shou puerh. All that and their elaborate farming techniques. Read about it HERE; too long for me to get into. The amount of awards and accolades this outfit has earned would fill its own blog.

Earlier this autumn, Kei got in touch with me to try some of their tea. I zeroed in on two products. Both were two different versions of the same tea; my tea blogging muse’s meal ticket. Both were called Issaku, and both were fukamushi (“deep-steamed”) sencha. The plain version was a shincha—meaning: made from young leaves plucked in the early spring. The other? The same thing, but the young leaves were then put in cold storage for a half a year.

This method was called kuradashi (“taken from the granary”), and it was a way of aging green tea without it growing stale. Traditional methods for making kuradashi sencha or matcha usually involved a clay pot and storing in a cool, dark room. However, on a macro-level, the industrious Arahataen group took things to another level.

There was more to this tea . . . but I’ll get back to that.

Both arrived within a week of the query.

For brewing, I decided to approach both the same way. The website recommended a steep of one minute in 175F water. Leaf-to-water ratio, similar to western style. I adhered to these pretty strictly. The area where I deviated was in the brewing vessels. I decided to use two Ceylon steeper cups and a Cha Hai filter to get the job done. I didn’t have two Japanese pots in which to do a side-by-side. This was a bad idea. I made a mess.

The leaves for this were cut pretty small, but there were longer “spider leg” reeds amidst the fray. The batch was bright green—bold in color—and gave off a very strong, welcoming scent. Sweetness with a tickle of vegetation acted as the intro to a wonderful springtime wilderness aroma. I could tell just from the smell that it would make for a heavy, savory, and delicious broth.

The Issaku brewed up just like I thought it would—a THICC radioactive green broth with an almost “melted citrus zest” smell to it on the steam. Some leaf particulates, alas, made it into the brew because my filtering skills weren’t exactly wizard-level. However, even with my mishaps, the brew was delicious—savory from start to finish with a layer of sweetness just out of sight. The finish coated the mouth in a blanket of wilderness grass, and that earlier citrus zest steam-lean remained on the palate for minutes after. The huigan (“comeback sweetness”) reminded me of the throat-coating effect of brewed fennel seed.

When I received this tea, I honestly thought it was just going to be the aged Issaku. Nothing more, nothing less. I thought the “22 Karat” in the name was just that . . . a name. Oh, was I wrong; should’ve read the label more carefully.

Not only was it not just aged green tea, but it had the added splendor of 22 karat gold flakes. Such an extravagance was usually added to special sencha batches for special gifts or for tea to sip to usher in the new year. The gold flakes were called kinpaku-cha. They weren’t really there to contribute flavor, more like a fancy garnish. Wait, scratch that. The fanciest garnish.

The leaf cut on this was about the same as the younger version. The color also hadn’t faded in the time it’d been aging. The only difference was in the smell . . . and the garnish. The gold flakes in the fray made it look like a green tea that was served at a bachelor party. Flakes glittered in spots where you wouldn’t expect glitter. And if anyone knows anything about glitter; it gets everywhere. The aroma was not as spring-like and punchy as the younger version, but it made up for that in a hunkered-down, dug-in sweetness. The character was smoother and deeper.

The older Issaku also brewed up brothy, but not quite as dark green as the younger version. The steam aroma also had a lighter delivery to it. On taste, this was definitely a different beast. Not as savory, not as heavy, but somehow more nuanced. Maybe even layered. The sweetness was also dialed up a notch or two, which I appreciated. Could I taste the gold? Well, no. I’ve never actually licked gold. Nor could I tell anyone if it contributed to flavor. (Too poor.) But the aged sencha aspects? Oh yeah, this tased like another kuradashi sencha I tried, only sweeter and less woody.

Which did I like better? The newer or the older? Honestly, it depends on the time of day. As an early morning beverage, I would want the shincha version. It’s sweet punchiness would rouse me rather quickly. For a late-afternoon bit of indulgence? Definitely the 22 Karat. It’s smoother, calmer, and more seasoned, but not as rich. (The other meaning of “rich”.) In short, they each have their own merits in equal measure.

I would definitely want to buy a monocle when diving into these two side by side. Eh, maybe two. Meh, screw it, I wear glasses. Close enough.

We’re not exactly a “fancy” operation around here.

To buy Issaku, go HERE.

To buy 22 Karat Gold, go HERE.

Leave a Reply