Earlier this year, a fellow tea blogger sent me information on an Indian tea growing region I’d never heard of.

A place filled with old(er) growth, semi-wild assamica forests, which bordered Assam to the East. The state: Manipur. I knew nothing about this Indian state, other than the fact that it bordered Myanmar. That and it was well within the zone with which the Indian strain of Camellia sinensis var. assamica (a variety and subspecies of tea tree) grew plentifully. For some reason, I shrugged at this. Mainly because of the “wild” claim. How wild could these trees be, anyway?

I didn’t give it much thought until I ran across a social media profile for a company called Ketlee. As part of their wares, they happened to have teas available from Manipur. In fact, they were made from the very, allegedly, wild trees the friend had told me about. Ketlee worked closely with an outfit called Forest Pick Wild Tea.

Their mission was simple: to make an effort at propagating and processing teas from the feral-looking forests dotting the landscape. People who resided in these pockets of tea tree growth weren’t accustomed to farming, and traversing the region into these assamica forests was arduous. Plus, there was the added question of how such forests even came to be. But I’ll get to that.

Ketlee didn’t just carry the normal products from the Forest Pick line—ooooooh no—they procured some of the weirder stuff as well. And, naturally, those are the ones I gravitated to. Particularly, the sheng “puerh” style tea made from those suspicious trees.

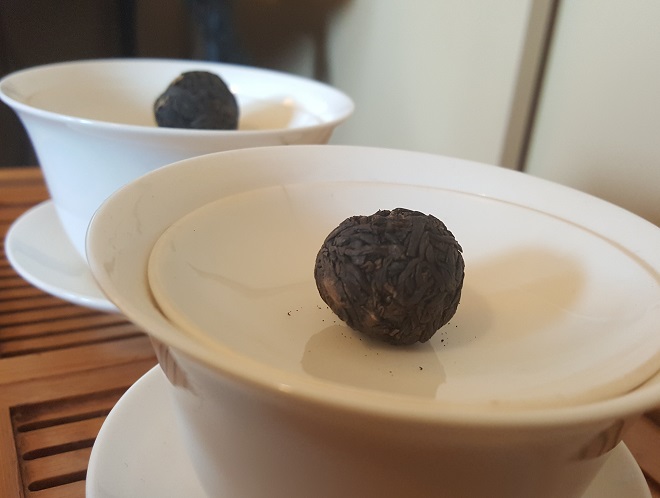

I got in touch with Ketlee before the summer kicked into high gear. By the time I did, though, they had sold out of the “puerh” cakes they’d commissioned. However, I was able to squeeze a few balls out of them. Tea balls, that’s what I meant. One was processed as a white tea; the other as a sheng “puerh”. I finally received them, and got around to trying them, later that month.

What’s funny is that both balls looked very similar—like fraternal tea twins. The only way to differentiate the white tea ball and the sheng ball was to look closely. The white tea ball was larger with a few pale needles poking through, whereas the sheng ball was smaller. Neither gave off much of a dry leaf aroma. The white tea smelled like . . . forest. While the “puerh” smelled like the faint embers of a scorched forest floor.

For brewing, Ketlee did provide some brewing instructions for each tea, but allowed a lot of wiggle room for experimentation. I opted for something in between gongfu and Western style; one steep for each ball (the whole 7-gram ball), and a one-minute steep with water brought to near a boil. A safe enough approach for my tastes and sanity.

The liquor for the white tea brewed super dark. The original product description said something along the lines of a dark golden liquor, but this was almost full-on black tea mahogany. I owed some of that to the fact that I used the entire ball, but that is what one is supposed to do with gongfu . . . right? I guess I should’ve used half.

The steam off the liquor smelled roasty, almost like a dark roast Dong Ding—only older. I was definitely worried about the taste at this point in the flight. On first sip, that was assuaged! Sure, there was a bit of sheng-y bitterness on the forefront, but that relaxed to a sage-y, mountainous note in the middle. The finish was toasty, but not overly burnt as I’d feared. But I do think some measure of over-steaming was done to get it into the requisite ball shape.

Dragon Pearl Indian “Gushu Puerh”

This one surprised me the most. (Spoiler alert.)

I expected something along the lines of a burly delivery like the white tea. After all, as with the white tea ball, I used the entire ball! That’s right, balls deep. (Sorry, had to go there. Okay . . . I didn’t have to, but I wanted to.)

The liquor brewed up lighter than the white, to a requisite sheng puerh bold amber. The steam aroma resembled the white as well in the slightly roasty hint, but far dialed back. Earthy tones played with my nostrils like woodwind instruments. On first sip . . .

No other way to put it, I felt like I was tasting a sheng puerh. Well, okay, not “puerh” in the strictest, palatial sense. It had similar notes to a border sheng cha, like a young Myanmar raw from Kokang. Notes of straw, wildflowers, and wind-swept hay. All held together by a periphery of melon rind.

Verdict, short version: the sheng ball was my absolute favorite. It was very much what the makers and vendors aspired to create. And—to date—it was probably the truest sheng cha I’ve tasted out of greater India. Sure, the one I tried from Tamil Nadu was more sheng-y to the taste, but it was also made from younger assamica material.

And speaking of age and wildness . . . time to address the elephant in the room. How wild and old were these Manipur tea trees? And if legitimate, how did they get there?

Theories abound as to the origin of these feral forest pockets. The most popular one I heard from one of my Assamese contacts was that they were early test plots planted by the British as early as the 1750s. However, that wouldn’t explain the veritable size of some of these tree trunks. Yet the way the trees appeared ornamental lent credence to the claim that they must have started life as planned gardens. Whether or not they came from seed or grafts, though, is anyone’s guess.

My theory is a bit more outlandish than that, and I only have my gut to go on. No, literally, my actual stomach plays a role in this. Trying these teas, and a few others from the region, had an interesting effect on me. After trying even one of the teas, I immediately grew hungry—like . . . famished. Tummy rumbles and all. If I didn’t eat something prior to trying said “wild” teas, my hands started shaking.

I read somewhere that Yunnan locals don’t drink teas made from actual old growth wild trees because it makes them sick. I couldn’t find any medical documents that corroborated this, but it was a common enough claim that I found it mentioned on a few vendor websites. This led reputable puerh or Yunnan tea sellers to not carry teas made from truly wild growth material. Not that many farmers in Yunnan actually produced from them.

Now, I didn’t get sick from the Manipur stuff, but it certainly had an effect. Wether or not it was due to their wildness, or their “intense cha qi”, something was up with those trees. Something that set them apart from your average, run-o’-the-mill, garden variety assamica.

Which brings me to my theory.

As I expounded in an outlandish article back in the Spring, I believed the assamica variety originated in and around the Indian subcontinent—probably somewhere around Tibet or modern-day Myanmar. I also theorized that the expansion of the Indus Valley Civilization, and later kingdoms, led to waves of agricultural migration. I have no direct evidence to support this claim, only heresay, but I believe the presence of semi-feral, old growth gardens in Manipur are byproducts of those earlier migrations.

Saying as much probably takes a lot balls.

Well . . . I drank two.

How do you like them pearls?

To buy the White Tea Dragon Pearl, go HERE.

To buy the Sheng Puerh Style Dragon Pearl, go HERE.

Leave a Reply