Several months ago, I had a conversation with a fellow tea nerd about the origin of the tea tree. Y’know, small talk. During the dialogue, he uttered the following assertion that made my imagination boil over like an unrestrained kettle.

No one had found the “god” tea tree, yet. Meaning: the tree from which all varieties, subspecies, and cultivated varieties stemmed. Naturally, for a long-standing, amateur student of the leaf, the notion was one that I held near and dear. I just hadn’t heard it put so succinctly

Why did the origin of the tea tree tickle my whimsy gland so? Well, before I dove into tea research, I was a bit of a mythology buff. With that came an exploration of mythological botany.

The apple from the Tree of Knowledge, the pomegranate of Hades, the World Tree itself, world mythological traditions have a love affair with fantasy flora. Our beloved tea tree happens to be a real one, and myths have spawned around how humans cultivated and processed it. Yet so little is known about how that all started.

Science, however, is slowly catching up with folklore, and I’ve somehow been on the periphery of some of those discoveries. Little bits and pieces of data and determination have shed glimpses of light in the mysterious chasm that is tea history. Theories abound!

And I’ve developed one of my own: a tea myth theory—if you will—regarding the origins of the supposed “god” tea plant. The (albeit) disparate research I cite from here on in came to me by accident. Hardly any of it is concrete, but it’s difficult to chock it all up to coincidence. And I don’t believe in coincidences.

Some of this may be a tad far-fetched, but if you’re a regular reader of this tea blog, you know that’s par for course. So, bear with me as I explore this floral fever dream. Let’s start with a couple of unrelated conversations I had a few years ago.

At a tea party, I remember discussing tribal Indian tea with a vendor friend. She’d mentioned that she’d been to Arunachal Pradesh and had a similar tea to the one I described. That wasn’t the interesting part, though. What she followed up with made my eyebrow arch—only one. According to her, the locals claimed that their assamica trees hailed from Tibet.

Not possible. The only things that grew in Tibet were . . . uh . . . Tibetans. And yaks. And the butter of yaks. (Shows what I knew.)

Any tea found up there came from China; Sichuan and Guanxi, more than likely. This friend merely shrugged at my doubt, and said that was simply what she heard.

Around the same time, I found myself in a rather in-depth conversation with a tea elder. He mentioned that he was doing some research on ancient kingdoms that existed along the Yunnan provincial border. This fascinated me because said border was always traditionally porous, which explains why northern parts of India, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos all had tribal tea making traditions that were similar to Yunnanese puerh.

I don’t recall the specifics of his research, and I think he kept most of it close the proverbial hip for propriety’s sake. Which I respected. The talk did make me wonder if such kingdoms shared traditions, and if that explained why tea forests were so plentiful because of that exchange. Like some kind of ancient Johnny Appleseed complex at work. I even fancied turning such a musing into a story at one point.

Over the ensuing years I didn’t give this thought experiment much . . . well . . . thought. But it did subconsciously affect my narrative in articles to come. Where before my focus had been notching off strange new teas—and it still is that to some exent—it gradually took on a deeper research bend. Whether by accident or design, who knows? My muse is a fickle twerp.

Then, this year, a few occurrences brought those old conversations back to the forefront. First, a science paper made the rounds on Facebook, making the bold assertion that—not only was the assamica tea tree variety cultivated independently in three different places—but also that there were three distinct subspecies of that variety. One was already known; Camellia sinensis var. assamica ssp. lasiocalyx—the Cambodian strain. However, due to recent genetic data, the same could be said for the China type—the Yunnanese strain—and the Indian strain.

Conventional wisdom up until that point stated that while the assamica variety was named for the Indian state of Assam, it actually hailed from Yunnan. After all, that was the uncontested birthplace of tea . . . right?

Well . . .

Due to the new information, that could no longer be a fully supported conclusion. For there to be three distinct subspecies of the same variety . . . of the same species . . . folks in those three regions cultivated, bred, cross-bred, and tinkered with the plant separated from other influences. But the original strain had to spread from somewhere. Finding the origin of that cultivation spread proved difficult, though, since there weren’t any truly wild tea forests in which to map said migration.

Or were there?

Shortly after that science paper percolated, an article appeared in World Tea News.

An alleged wild tea forest had been “discovered” in the wilds of Arunachal Pradesh, a state in India that—itself—was a bit of an enigma. And the subject of one of my earlier tea tree origin conversations. If true, the discovery would throw off all conventional wisdom about where or who cultivated the tea tree first. As mentioned in the scientific study, the origin of the assamica variety was often in dispute. And one of the possible, alternative origin theories was the Himalayas. Possibly even Tibet.

But as we established, nothing like that could grow in Tibet . . . right?

Well . . .

Back in January, tea vendor friends—ZhenTea—posted a photo of a tea garden. In Tibet. Shortly after that bombshell, they released the latest installment of their newsletter, CHAREN, detailing a visit to that tea garden situated on Yigong Lake. Stranger still? It wasn’t the only one. Granted, it wasn’t thousands of years old, nor were they cultivating assamica. Yet it did prove that, in some fertile pockets of that high-altitude territory, tea could grow.

By now, you—fair reader—are probably thinking that all of this is just meandering, unrelated bits of research. What does this at all have to do with the ur-species of Camellia sinensis? Also, what about the other two varieties besides assamica?

I’m getting to that.

First, let me ask you all a question: what is considered the first true tea myth? The origin of tea drinking?

That’s right, Shennong.

A tea leaf fell into his cup of hot water and gave him abundant health, and later on turned his skin translucent . . . or something. No true tea “scholar” believes that this was the actual origin of tea drinking, but there is some evidence to suggest that tea leaves were imbibed in and around that time period. The fact that I want to hone in on, though, was the alleged timeframe in which Shennong lived—roughly around 2700 B.C.

Do you know who else purportedly lived around that timeframe?

King Gilgamesh of Uruk. In Mesopotamia.

This may seem like a stretch to make Gigamesh a contemporary of Shennong, but I have my reasons for doing so. A few years ago, I ran into an article summarizing Gilgamesh’s encounter with an immortal man named Utnapishtim. Think of him as the Sumerian Noah.

In the article, Utnapishtim relayed to Gilgamesh how he saved the seeds of life from the Great Flood unleashed by the gods. He distracted them by . . . brewing tea. The aroma of the brew apparently distracted them long enough for his wee boat to escape to parts unknown. For his craftiness and tenacity, he and his wife were rewarded with immortality.

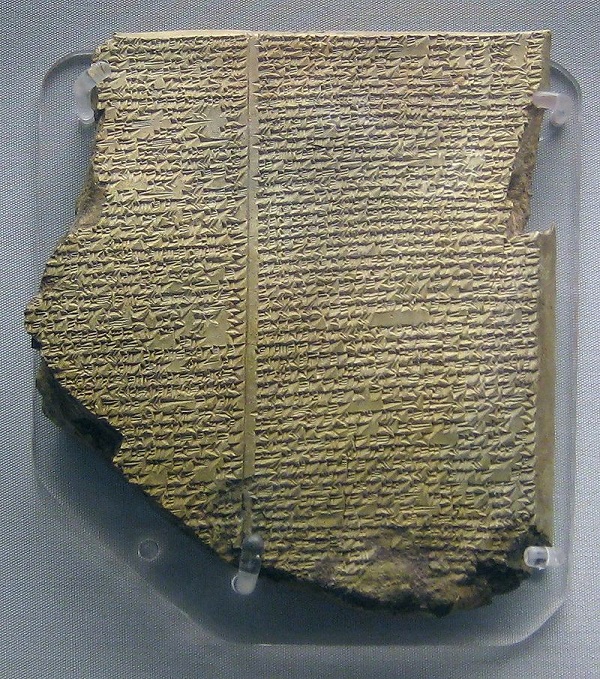

Naturally, I had to consult the actual tablets to see if this interpretation was accurate. Tablet XI of the tale reported those events a little differently. Instead of “brewing tea”, Utnapishtim actually lit a bunch of herbs as incense, cooked up some meat, and that aroma distracted the gods.

So, how did these other articles interpret this as Utnapishtim having brewed tea? Something that happened in later tablets might shed light on that. After Gilgamesh conversed with Utnapishtim, the flood survivor told the Sumerian king of a plant that would grant him youth, but he had to fetch it at the bottom of the ocean. Due to a tragic mishap involving a snake, he lost the plant. Or did he?

Let’s talk about where Utnapishtim was from for a second.

In the Gilgamesh story, Utnapishtim goes by many names, and is credited with either being the pre-flood king of the Sumerian city of Shuruppak, or some other ruler of the near-East. The supposed “Flood” took place around 2900 B.C. This also coincides with other possible dates for other deluge myths in the East, including the one that Noah survived, and also a similar myth hailing from China—the legend of Gun-Yu.

Where Utnapishtim ended up, though, is more important. The Gilgamesh epic states he and his wife ended up in Dilmun. Think of it as the Babylonian Eden. Archeological evidence states that Dilmun actually existed and corresponds with modern day Bahrain.

While there was, indeed, a port civilization called Dilmun on that very island, it may not be the same Dilmun mentioned in Gilgamesh. I ran across another article that posits another possible location for Dilmun. It hypothesized that the mythical garden-city was perhaps situated within—or north of—where the Indus Valley Civilization thrived. This civilization (Harappa) and ancient Sumer were trading partners. Dilmun sometimes acted as a go-between.

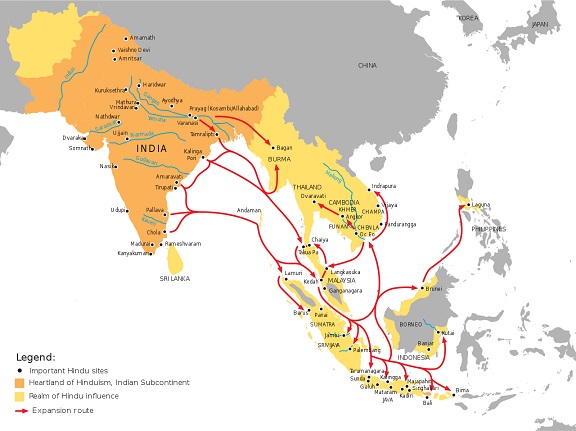

In the ensuing millennia and centuries, traditions from the Indus Valley migrated eastward. This pattern continued even through the rise of Hinduism, and through the spread of its influence.

It isn’t that much of a stretch to think that, maybe, agricultural techniques spread around the same time. With it, the cultivation of assamica spread, or so I believe.

As for the other tea tree varieties? Small leaf sinensis or mid-range cambodiensis?

I dunno.

What I do know is that the first big clue to finding the “god” tea tree is following the lineage of assamica as far back as it can go. While the first variety split of the species occurred (possibly) 20,000 years ago, the three-way assamica split occurred far more recently than that. How recent? Somewhere in the ballpark of 2900 B.C. and 2500 B.C., within the period of time a series of deluges occurred, and when Shennong and Gilgamesh were traipsing around looking for (and drinking) plants to make themselves immortal.

Far-fetched?

Yeah, but no more far-fetched than a dude accidentally drinking hot water with a leaf in it.

Leave a Reply