I don’t consider it spring until I’ve had a first flush Darjeeling in my mouth. This year, though, it took me a little longer to get to my “stash” of first flush Darjeelings. Most years, the family Lochan sends me a few to get the ol’ palate revved up for the year to come. And, as with most years, I dive right in. First flush Darjeelings are a special treat to this ol’ tea blogger. Unlike most “black teas”, Darjeeling first flushes aren’t fully oxidized. That’s why they maintain a very “green” palette, and a very floral palate.

Who can you blame for that?

Ja. That’s right.

First flush Darjeelings used to resemble second and autumnal flush Darjeelings; both in appearance and oxidation. However, since the biggest Western importer a few decades back was Germany, they had a sizable influence over how said tea was processed. They wanted to emphasize the natural aromatics of the region when the spring pluck occurred; when the sweet floweriness was the most pronounced. Enter: the greener, more aromatic first flush.

This year, I got a few of the usual suspects from the Lochans—Giddapahar, Rohini, Avongrove, etc. But there were a few in there that caught a second glace for another reason. I’d never heard of them.

Ringtong, Upper Fagu, and Hillton: of those three, only Upper Fagu had crossed my path before, and I didn’t give it much thought. If I was going to do an immediate tasting, it would be on these three teas, if only for the mystery factor. Alas . . . as per usual . . . it would take me a couple of months to get around to these. And when I did . . .

I tried these three teas in ways . . . um . . . unbecoming of a review sample. As in, I treated ‘em like any ol’ get-through-the-day tea. Which, in all honesty, was still a fair approach; after all, if they couldn’t last through a normal day, what good were they? In short, this will be a revelation on three fronts: you all will see how I brew tea on a normal work day, you’ll see me struggle through information about gardens I know very little about, and you’ll see me try a new way to keep taster notes.

I guess the last bit will be pretty short; I recorded the taster notes as memos to my phone. Voice dictation got a little weird. One sentence came out as: You the one brood really strong.

I have no idea what I was trying to say.

First up was a first flush from the Ringtong estate. Vivek Lochan urged me to try this one first. It hailed from a garden that had reopened after a 17-year hiatus. The reason for the closure? The factory burned to the ground in a bout of labor unrest in 1996. Since then, it changed owners, and geared back up for production in 2017. This was only its second year of full(-ish) production.

The leaves looked like any other first flush out there.

Green as all heck, broken leaf, and brimming with an aroma of sweetness, nuttiness, and something that reminded me of maple glazed trail mix. Is that a thing? No? Why is that not a thing?!

For brewing I’m . . . not sure how much leaf I used, probably somewhere between six to ten grams. It was my morning; fairly early for me, no less. I basically just opened up the sample bag, and threw all the leaf material into my twelve-ounce tumbler. Scalding hot water steeped those leafy bits for something like—oh—five minutes? Ten? I dunno, I was busy making breakfast.

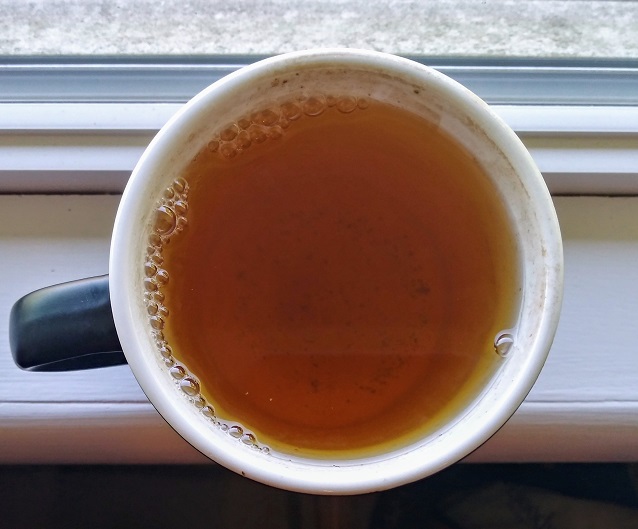

As expected from my half-assed approach, the brew infused strong! Yet it still had a very gentle floral and sweet delivery. That was immediately followed up by a far louder nut-sweet top note. A nice soft astringency trailed behind and wrapped everything up in a nice, weird li’l palatial bow.

Well, that was different, I thought. Too different.

Those same notes showed up in a strong second infusion as well, while I was at work.

I probably would’ve garnered a more nuanced profile had I brewed it lighter. Whatever, though, I was having a heckuva work day. And a strong Darjeeling fueled me. The peculiarity of the nut-sweetness even existing in the brew stuck with me, though.

The next day, I dipped into the Upper Fagu first flush. As I mentioned briefly above, I could find next to nothing on this garden. There was plenty of information on a Lower Fagu tea estate, complete with vacation destination bungalow packages, but nothing on an Upper. I had to shoot off one (of two) emails to Vivek to learn more.

He had very little information on it also, but he was able to provide the following blurb:

“Upper Fagu is a small tea garden located in the Kalimpong district of West Bengal, India. It is situated on the eastern part of Chel River, Sombaray Bazar. The area is bordered in the south by Bhuttabari forest area, in the north by Ahaley Busty, and in the east by Mission Hill Tea Estate.

Upper Fagu Tea Estate has approx 103 hectares under high quality tea. This area is quite away from Darjeeling tea plantations, but has a lot of potential for producing good quality teas.”

I knew none of those places, rivers, or whatever, but I could understand that—by Darjeeling garden standards—103 hectares was pretty normal sized. Roughly 250 acres. About the same as the Arya tea estate, and even a little larger than Giddapahar. However, the fact that it was far removed from the main cluster of Darjeeling gardens was an interesting fact.

This first flush offering had leaves that looked moderately the same as others I had tried, but the machine-cut pieces were a smidge smaller than the typical batch. The color palette was the same, green as could be with a tinge of brown around the edges—evidence of oxidation. And, just like the Ringtong offering, a peculiar nut-sweet aroma was imparted by the leaf material.

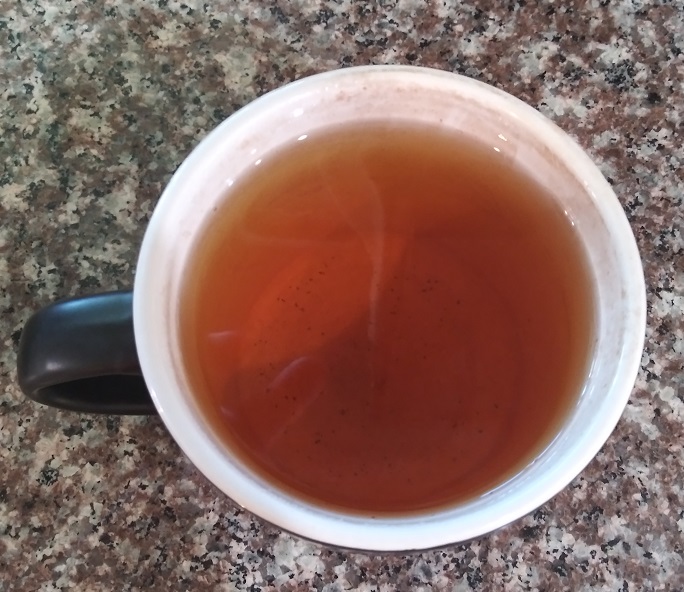

The liquor colored to a typical light-to-medium amber, and the steam aroma was quintessentially first flush Darjeeling.

Naughtily floral with a bit of something extra. The taste, though—while at first similar to the aroma—did something different. Within the first sip, it almost seemed like nothing much was there (palatably), but then it shyly opened up to some of the typical notes. Yet they were shrouded in that peculiar nut-sweetness and soft astringency. Just like the prior day’s brew. Albeit, this was nowhere near as loud. In fact, I kinda liked that it wasn’t.

The second infusion at work turned out the same, note-for-note.

For the third (and last) day, things got really weird.

The Hillton (or Ambiok) tea estate was situated relatively near to the Upper Fagu garden, but it was considerably larger—by nearly 100 acres. The “Hillton” in the name represents a partition of the garden that rests on a higher-altitude plot, as the “hill” in the name would suggest. This first flush came exclusively from that plot.

I’ll spare you the redundancy by saying the leaves looked exactly like the others. Perhaps a bit more on the “green” side. The aroma was a little bit more floral, more in line with what I was used to from a first flush.

When brewed, though, it delivered a far more bitter forefront than the other FFs, but that was immediately stomped out by a literal taste of “bouquet”. I wondered for a second if I’d over-steeped it, but I remember checking the time closely.

Further in the sip, more of the floral and “green” aspects came through. The finish was astringent, but with a lot more strength to it than the others. As if this had been made from assamica leaf material.

The second steep at work was even more bizarre.

It was earthy. Like . . . sheng puerh earthy with a heather finish.

At the end of those three days, I was at a bit of a loss. I expected a simple, typical first flush Darjeeling experience. What I got was something else entirely. Like I journeyed down the same path I always did, but someone paved over the familiar landmarks. I was lost.

None of those palatial profiles resembled anything I’d run into before, and I could only think of one reason why. First flush Darjeelings were produced a certain way to emphasize the aromatics present in the terroir. However, that’s been changing lately. No, this is not yet another whiny article on the effects of climate change on tea growing regions. (Although, that is a thing.) Rather, Darjeeling gardens have been changing up the way they process first flush teas, as if to adapt to changing times, palates, and . . . yes . . . climate. And the biggest change seems to be occurring in the first step in the tea making process: the wither.

Up until recently, Indian tea producers were known for subjecting the green leaf that comes into the various factories to a more industrialized withering process. That being: removing more moisture so as to ready them for faster rolling and oxidation. The only way to do this is to introduce the fresh leaf to a hard wither. Meaning: lengthening the time it takes for the leaves to turn green and crispy, usually around four hours under room-temperature fans—weather permitting.

This is especially true with first flush Darjeelings. They are introduced to a hardened withering stage, which—yes—dries them out early, but also shortens the oxidation stage. (I.e. the enzymatic “browning” stage.) So, on the best of days, first flush Darjeeling “black teas” are actually only partially-to-mid-oxidized. As opposed to standard black teas, which are completely oxidized. In this way, they have more in common with oolongs than black teas—albeit without the fixing, bruising, and complicated rolling/roasting.

Why do I bring all that up? (Especially since, if you’re reading this blog, you already know all this crap.) Well, as mentioned above, things have been changing, and—for the last couple of years—it’s been very apparent in the way first flush Darjeelings taste. And I believe the “blame” rests solely on the wither. That being, softer withers.

It was first readily apparent in a first flush I tried from Giddapahar this year.

But it was also apparent in three other first flush teas I tried over the last week from the gardens I’d never heard of. In the production of green tea and oolongs, leaves are subjected to a softer withering phase. Some of the moisture is still left in the leaf, so as to maintain pliability when they’re introduced to the rolling and fixing stages. A softer withering phase is usually indicated by the shortened amount of the time the leaves are subjected to it.

Throughout much of the winter, and well into spring, the Darjeeling region had experienced a cold snap. Temperatures didn’t dip above the 40s (Fahrenheit) until mid-April. I cross-referenced AccuWeather results and with information provided by other Darjeeling providers. They all mentioned how the first flush season got a very late start this year. Lowland Darjeeling gardens usually start their first flush production in late-Feb, and even they didn’t gear up until well into March.

What does this have to do with the withering? Well, I suspect that—regional industry wide—gardens had to make up for lost time, and shortened the time it took to wither the leaves. Due to weather and delays, they inadvertently (and collectively) softened the withers on their first flush offerings. All leading to wild and varied results that deviated from the norm.

And I can’t say I mind. I enjoyed every one of those weird brews over the three days I had them. They were a welcomed change from the status-quo. While I was (and still am) a fan of the loud, aromatic first flush of yore, I was happy to have my palatial paradigm shaken.

If only for a season.

For a list of first flush 2019 Darjeelings currently available from Lochan Tea, go HERE.

Leave a Reply