This is an awkward statement to make right now . . . but . . . I’ve been on a bit of a Darjeeling kick, lately.

Especially given recent (at the time of this writing) news reports. And I’m not going to delve into any of that. This is a tea blog; I tell tea stories. And this is—for once—a happy tea story about Darjeeling. A “wild” one.

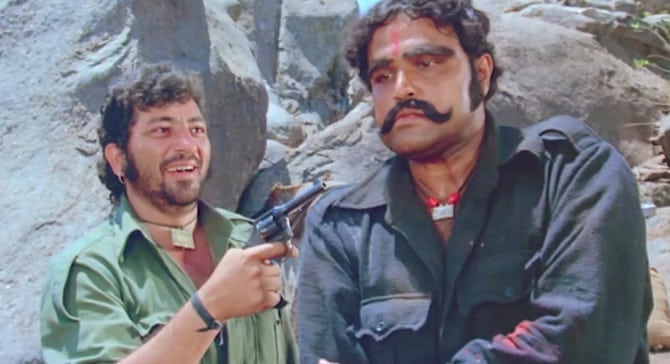

Back in May, I was contacted by Rajiv Lochan of Lochan Tea. In it, he practically begged me to cover a tea garden I’d already written about. He said if their teas didn’t get any publicity that he would be—and I quote—“shot Western style.” For some reason, an image of the curry Western, Sholay, popped into my head.

The garden in question was Rungneet (sometimes referred to as Kanchan View). I covered it to great extent a year ago; there really wasn’t much more to tell. The troubled garden’s history was microcosmic of the Darjeeling region as a whole. It was lovely, it had history, but there was a sense of fading majesty there.

While they still produced teas, and they possessed the ideal flavor profile of other Darjeelings—from what I tried—I didn’t think there was much more of a story there. Any follow-up article would be nothing but taster notes. Rajiv, though, wouldn’t take “No!” for an answer . . . as is his custom.

He sent me photos of excursions he took to the garden with several tourists. That was one of his goals: to turn Rungneet into a Darjeeling tea tourism destination. One of the photos caught my eye. Dan “World Tea Tours” Robertson stood next to the largest, wildest, Northern Indian clonal I’d ever seen.

Dan Robertson is not a small man. If “Dans” were a form of measurement, that tea tree was probably three Dans. It was huge, wild-looking, and all I could think was, “I want to drink the heck outta those leaves!”

Rungneet had a problem that was also its most unique feature. About half the garden was dotted with un-pruned, un-tended tea trees. Due to a changing roster of owners, financial finagling, and a shortage of workers, some of the trees were simply left to grow wild. Many of them returned to—what the Chinese would call—a “semi-feral” state. Meaning: sure, they were still present in a man-made garden, but due to no man-made interruption, they returned to something close to their natural state. In all of Darjeeling, this was mostly unheard of. Tea trees left alone had existed for fifty years in such a “wild” state.

So, I said to Rajiv, “If you can get me a tea made from those wild tea trees, you have yourself a story.”

The next day, Rajiv made contact with the garden manager. A couple of days after that, he informed me that a small batch of semi-wild, second flush Rungneet was being processed and invoiced. A couple of weeks after that, he shared the discovery with the social media world.

Rajiv likened it to a Yunnan Dian Hong, due to some of the “old tree” assamica notes that showed up in the brew. Granted, these weren’t assamica we were dealing with here, but rather small leaf sinensis clonals. However, I could see how the unrestrained nature of the wilder bushes might impart those flavor characteristics.

Shortly after that, Rajiv said my small batch was on its way, along with a few other Darjeelings. And, sure enough, the box arrived in a punctual manner. One problem, though . . .

Indeed, there were a lot of Darjeelings in that box. But there was no Rungneet.

My eye twitched. The “lizard brain” part of me thought the small batch turned out so well that Rajiv decided to keep it all for himself. But I kept those thoughts at bay (until now . . . in this writing). I wrote him about the missing sample. In communicating with him and his son, Vivek, I learned that there’d been a mix-up. Another package was dispatched.

In it . . . was the semi-wild Rungneet.

Yes, I tore it open the day it came in.

The leaves were gorgeous and old-seeming. Their cut ranged from small to large, and there was no real uniformity to them. It lent credence to the “wild” claim. Rajiv assured me that, while they were machine cut, they were—unlike most Darjeeling second flushes—hand-rolled. And that showed.

Most of the leaves were whole, wild-looking, quite large, and plump. That and some of the leaves were not just gold-tipped, but . . . full-on gold all around. The aroma also differed from just about every other Darjeeling I’d sipped in my decade-long tea journey. The dried leaves gave off a smell that reminded me of oxidized Korean teas—nutty with a bit of muscatel on the trail scent. There was also a bit of Phoenix Mountain sharpness mixed with a smidge Yunnan earthiness, too.

Yeah . . . I brewed it up immediately.

The liquor colored to a medium oolong amber. On par, maybe lighter, than a Korean Hwangcha. However, it possessed the boldest, most layered flavor profile of any Darjeeling I’d ever encountered. Sharp, Dan Cong black tea notes took point, Korean oxidized tea nuttiness dominated the middle, and it finished with a shred of muscatel on the back. Per Rajiv’s description, a Yunnan lean permeated throughout. And most noteworthy—from a manly standpoint— there was a lingering huigan of sweet tobacco.

Lochan Tea also sent along two other Darjeelings to pair with the wild Rungneet—at Rajiv’s behest. He wanted to hear my thoughts about how it faired when put head-to-head with Imperial Muscatel (from Giddapahar) and Muscatel Delight (from Goomtee). Two heavy-hitting tea gardens when it came to topnotch Darjeeling quality.

The Giddapahar smelled the boldest of straight muscatel, and while the leaves did look hand-rolled, they were also given a smaller cut. As for the dry aroma, I picked up on whiffy-notes of grapes, olive leaf, and some echos of first flush floral spice. When brewed, it colored to a deep amber red with bold muscatel-smelling steam—sweet and spry. The aromatics carried over to the taste with a savory, grapy lean and a bit of astringency. Spice in the middle and a smidge of malt rounded out the cup. Par for course when it came to Darjeeling characteristics.

The Goomtee second flush was quite different. The leaves were larger, curlier, twistier—more hand-rolled in appearance. They looked like Fujian black tea leaves on first impression. Some gold-tipped pieces rounded out the menagerie. And while there was some muscatel to the scent, it was actually more earthy and Yunnan Dian Hong-ish on the back-end. Similar to the Rungneet. It also brewed up far darker than the Giddapahar or the Rungneet, imparting a brew that was Assam copper red. As for taste, it resembled a Monsoon flush: muscatel on the front, stone fruit and nuts in the middle, malted raisins on the descent, and a finish of toast and wood.

Comparing the three was like chronicling a taster note chart of Darjeeling nuances—Giddapahar on one extreme, Rungneet on the other, and Goomtee as the perfect fence-sitter. When it came to subjective enjoyment, though, I have to say the Rungneet won this little contest. If only for just how bizarre it was. The tasting experience was tied with the first time I sipped a Castleton Moonlight; it floored me. The other Darjeelings were still great, but this was another dimension altogether.

As I mentioned above, compared to other Darjeeling tea gardens, Rungneet is in a unique position. No other established garden has tea bushes as old as theirs that have grown semi-feral. That small batch of hand-rolled leaves proves that they pack quite a bit of flavor, which lends credence to the notion that Darjeeling clonals can go beyond the recommended “thirty-year” flavor threshold. That is, if the trees are left alone—save for plucking. No pruning.

This was a bold experiment, and I was happy to be on the palatial front lines of it. And now . . . *sigh* . . . I suppose we can’t finish this without addressing the elephant in the room.

At the time of this writing, the region of Darjeeling is entirely closed off from the outside world. I won’t even go into the specifics of it. The reasons are too long and varied, and the issues are far too complex. Those who have read my blog in the past already know where I stand on many of the issues, and as to many of the new ones that’ve cropped up . . . I’m a bit on the fence.

I do know one thing, though.

I’m a forty-year-old toilet cleaner from the right armpit of the United States. I was able to convince a Darjeeling wholesaler—who also managed his own tea garden—to persuade another tea garden to make a tea from semi-wild tea trees. All for the sake of putting words on my little corner of the Internet. Perhaps in that allegory, there’s an answer.

All one has to do is listen to the leaf.

Leave a Reply