Over the course of years, I’ve had strange relationships with many teas. I’m kind of a steep-slut that way. But none have been as ass-backwards as my journey with An Ji Bai Cha.

Image owned by Seven Cups

To those who’ve never heard of it, here’s the quick-‘n-dirty. An Ji Bai Cha is a famous (and ancient) green tea hailing from An Ji County, Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China. Its history is long and varied. The first mention of it dates as far back as the Song Dynasty. The emperor, Song Huizhong, made mention of “Bai Cha” in one of his famous writings on tea. Tea scholar Lu Yu, some centuries later, wrote about exquisite teas from the An Ji region. However, no one connected that the apparent “Bai Cha” the emperor talked about hailed from An Ji.

Now, I know what you folks familiar with Mandarin might be thinking: no, An Ji Bai Chai is not white tea, even though “Bai Cha” literally translates to “White Tea”. In fact, to this day, some vendors mistakenly categorize it as a white tea. From a strict processing standard, it’s not—it’s a green tea. The “white tea” in the name stems from the cultivar.

Image owned by Seven Cups

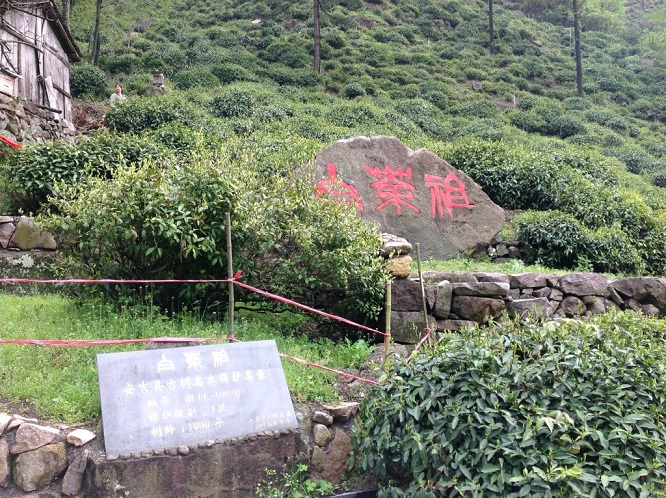

Bai Ye (“White Leaf”) #1 is a variety cultivated from a mutant strain of Camellia sinensis var. sinensis. The leaves for this strain are pale green, almost yellow in appearance. Centuries ago, when the albino plants were found, cuttings were taken from them and cultivated.

The Mother of all An Ji Bai Cha bushes!. Image owned by Seven Cups

It wasn’t until the 1980s until enough bushes had been cloned and grown to yield a sizable enough crop for commercial use.

From centuries ago to this very day, the tender young leaves are subjected to a kill-green phase, which makes it very much a green tea. Even if, by color and appearance, they resemble a white tea in every other respect. So, got that? It’s a green tea—full stop. And I’ve said as much on multiple occasions, but here’s the thing . . .

As much as I’ve ranted about it, it took me years to actually try it. In fact, the first version I ever tried from the An Ji Bai Cha cultivar . . . wasn’t even the heralded green tea. No, in 2016, I tried a black tea made from the Bai Ye #1.

At World Tea Expo in 2016, I was hanging out after hours with Seven Cups Fine Chinese Tea co-founder, Austin Hodge. He mentioned that he had an experimental black tea made by made by one of their partner farmers, Yu Shunhu. I begged for a smidge of some. He rolled his eyes and tossed me the bag.

Yu Shunhu was Seven Cup’s regular provider of a special An Ji Bai Cha green tea they called: “Ming Qian An Ji Bai Cha”. It was named thus because it was plucked and processed at the earliest possible time; right before the Qingming Festival, indicating the start of spring. And I hadn’t tried it, nor any An Ji Bai Cha, for that matter. Worse? Seven Cups sent me a sample of it back in 2014, and I forgot about it! I didn’t get around to trying the green tea until two years later, at another World Tea Expo after-party.

However, I still wanted to try Yu Shunhu’s An Ji Bai Cha, but not just that. I wanted to do a side-by-side tasting with the black tea they created. Unfortunately, I had no stores of the beta-batch left. Little did I know, though, that—in 2020—it became a part of Seven Cup’s tea roster. I begged them (again) for samples. And (again), they obliged.

Seven Cups recommended approaching both of these teas the same way. Water brought to a heat of 185F, and a first infusion of three minutes. Leaf ratio: a tablespoon and a half, basically a two-finger clump of leaves—eyeballed. I hadn’t approached the Hong like that the last time, instead opting for 190-to-full-boil, but this would be an interesting deviation.

When I finally tried this, it wasn’t the ideal time. Usually, the best time of year to sip a spring Chinese green is in the spring. However, my worries about timing were assuaged just smelling the bold, yellow-green leaves. Pan-fried green teas—when done right—have an almost-date-sugar-‘n-chestnut aroma to them, at least to me. This was no exception, save for the extra sweetness indicative of the cultivar. There was almost a vanilla bend to the aroma.

The liquor brewed up white tea pale, a mild yellow with a slightly vegetal—but overall floral—fragrance. I was actually quite surprised at the paleness to it, but the flavor countermanded that surprise with . . . even more surprise. A whole lotta big, honkin’ taste. It had a bit of bite to the initial sip, a slight slap of bitterness, but it smoothed out to its more sweeter profile. Vanilla was the clear top note. Or rather, honeysuckle dabbed in vanilla. At least, that’s what my brain was processing.

This resembled the earlier experiment I tried—in that it resembled nothing else in the black tea family. The leaves were medium-sized and twisty, like a Taiwanese black tea, but the aroma was more akin to a Fujianese black tea. The smell was clean, giving off a wood-sweet and vanilla vibe. So far, the vanilla bend was the linking factor between this and its greener sibling.

At the lighter temperature, this brewed up to the bolder side of amber. Very similar to a sun-dried Dian Hong, but the aroma remained in Keemun or Ming Hong territory with that backwoods, wild sweetness. There was even a creamy caress to the steam as it wafted its way to my nostrils. Like how a solf-lit, soft-core porn would smell. (Yes, vanilla as well!) The taste echoed all of what I said above. The flavor started off like any ol’ twisty leaf black tea—sweet, slightly astringent, yadda-yadda—but then drifted into notes more in line with smoother greens and whites. That whole honey-vanilla-lathered flower thing was there, just more pronounced in a heavier oxidation.

Following the side-by-side flight—while plenty tea drunk—a familiar notion hit my tea-fuzzed brain. I took the green tea and black tea leaves, and blended them together. The results were . . .

. . . Nothing anyone should ever replicate. Both of these teas are masterpieces on their own, but just on their own. Blending not recommended.

But—hey—this strange tea journey had to come to a close, somehow, in a fitting way.

To buy the Ming Qian An Ji Bai Cha, go HERE.

Alas, the Anji Hong is sold out, but you can learn about it HERE.

G.Norman

Sounds wonderful,I believe you would be a good tea guide.

Margo Hutchinson

What a story, sounds very technical but tastes good.