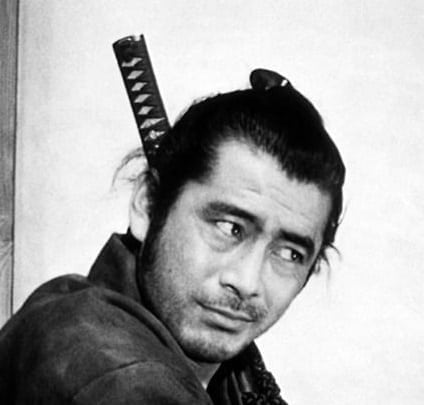

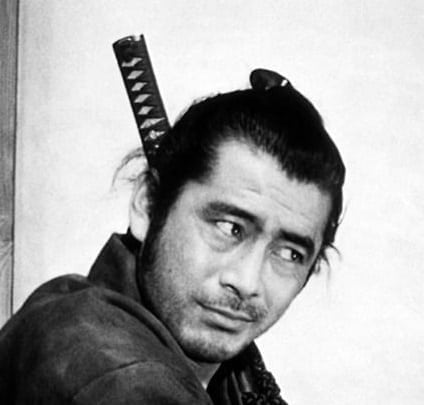

In the hierarchy of tea businesses, monthly tea subscription services are like man-buns.

Unless you have a really good reason for starting one—or your name is Toshiro Mifune—it is usually best not to. Since 2014, there has been a veritable surge of tea start-ups, and the route they’ve all chosen? You guessed it, the monthly subscription model. When I attended World Tea Expo that year, every new vendor present was either (a) trying to start one, or (b) “thinking” of starting one. And from a business perspective, it makes sense.

All a potential “monthly” vendor had to do was acquire enough wholesale product at cost in order to meet the demand of their current subscriber base. They could easily keep a tally of how much to purchase and when—i.e. once a month. This strategy kept costs low and overhead even. No gambling.

The problem?

With a glut of so many subscription services out there, and a dearth of people interested in tea, it’s hard to stand-out. A vendor would need to have a very unique angle to the strategy in order to stick out in the rough. And, no, custom blending doesn’t count. At least, not anymore.

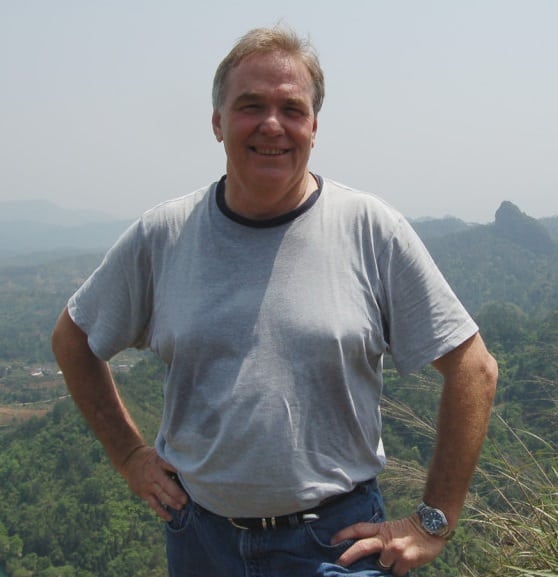

So, when I was approached by Tea Runners in June of this year, one can understand why I went into the conversation skeptical. I was approached by Charlie Ritchie, and—just from the initial email—I already liked the guy. His tone was conversational, jovial, and it didn’t come across as a normal cut-‘n-paste e-mail job. Even it if was, I couldn’t tell, so . . . go him! That and his replies to my queries were prompt and polite.

Tea Vendor Etiquette Level: Wizard.

After the initial message, I did a little research. I, at least, wanted to give this li’l start-up the benefit of the doubt before I turned my nose up. I went to their bio and saw . . .

Left to Right: Charlie Ritchie and Jewel Staite. Image owned by Tea Runners.

Wait a minute . . .

Read More

dirty version: the garden was founded in 1979 from the remnants of an old Lipton test plot. From three plants that survived a haphazard bonfire, horticulturalist Donnie Barrett started a tea garden that would later expand to 61,000 plants of various cultivars. He experimented with making his own tea in 1984 after a visit to China, and pretty much had to learn everything from scratch.

dirty version: the garden was founded in 1979 from the remnants of an old Lipton test plot. From three plants that survived a haphazard bonfire, horticulturalist Donnie Barrett started a tea garden that would later expand to 61,000 plants of various cultivars. He experimented with making his own tea in 1984 after a visit to China, and pretty much had to learn everything from scratch.

Editor’s Note: This is merely a thought exercise by the author. The opinions reflected in the below narrative do not reflect the opinions of the teaware on staff . . . or this editor, for that matter.

Editor’s Note: This is merely a thought exercise by the author. The opinions reflected in the below narrative do not reflect the opinions of the teaware on staff . . . or this editor, for that matter.